Math Is Fun Forum

You are not logged in.

- Topics: Active | Unanswered

#901 2021-05-05 00:07:40

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 48,424

Re: crème de la crème

867) Arthur Kornberg

Arthur Kornberg, (born March 3, 1918, Brooklyn, N.Y., U.S.—died Oct. 26, 2007, Stanford, Calif.), American biochemist and physician who received (with Severo Ochoa) the 1959 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine for discovering the means by which deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) molecules are duplicated in the bacterial cell, as well as the means for reconstructing this duplication process in the test tube.

At the U.S. National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Md. (1942–53), Kornberg directed research on enzymes and intermediary metabolism. He also helped discover the chemical reactions in the cell that result in the construction of flavine adenine dinucleotide (FAD) and diphosphopyridine nucleotide (DPN), coenzymes that are important hydrogen-carrying intermediaries in biological oxidations and reductions.

Appointed professor and director of the microbiology department at Washington University, St. Louis, Mo. (1953–59), he continued to study the way in which living organisms manufacture nucleotides, which consist of a nitrogen-containing organic base linked to a five-carbon sugar ring—ribose or deoxyribose—linked to a phosphate group. Nucleotides are the building blocks for the giant nucleic acids DNA and RNA (ribonucleic acid, which is essential to the construction of cell proteins according to the specifications dictated by the “message” contained in DNA).

This research led Kornberg directly to the problem of how nucleotides are strung together (polymerized) to form DNA molecules. Adding nucleotides “labeled” with radioactive isotopes to extracts prepared from cultures of the common intestinal bacterium ‘Escherichia coli’, he found (1956) evidence of an enzyme-catalyzed polymerization reaction. He isolated and purified an enzyme (now known as DNA polymerase) that—in combination with certain nucleotide building blocks—could produce precise replicas of short DNA molecules (known as primers) in a test tube.

Kornberg became a professor of biochemistry at Stanford University, Palo Alto, Calif., in 1959. From 1959 to 1969 he was department chairman. His writings include ‘Enzymatic Synthesis of DNA (1961)’. Kornberg’s son Roger D. Kornberg won the 2006 Nobel Prize for Chemistry. They became the sixth father-son tandem to win Nobel Prizes.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#902 2021-05-07 00:16:03

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 48,424

Re: crème de la crème

868) Severo Ochoa

Severo Ochoa, (born Sept. 24, 1905, Luarca, Spain—died Nov. 1, 1993, Madrid), biochemist and molecular biologist who received (with the American biochemist Arthur Kornberg) the 1959 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine for discovery of an enzyme in bacteria that enabled him to synthesize ribonucleic acid (RNA), a substance of central importance to the synthesis of proteins by the cell.

Ochoa was educated at the University of Madrid, where he received his M.D. in 1929. He then spent two years studying the biochemistry and physiology of muscle under the German biochemist Otto Meyerhof at the University of Heidelberg. He also served as head of the physiology division, Institute for Medical Research, at the University of Madrid (1935). He investigated the function in the body of thiamine (vitamin B1) at the University of Oxford (1938–41) and became a research associate in medicine (1942) and professor of pharmacology (1946) at New York University, New York City, where he became professor of biochemistry and chairman of the department in 1954. From 1974 to 1985 he was associated with the Roche Institute of Molecular Biology; thereafter he taught at the Autonomous University of Madrid. Ochoa became a U.S. citizen in 1956.

Ochoa made the discovery for which he received the Nobel Prize in 1955, while conducting research on high-energy phosphates. He named the enzyme he discovered polynucleotide phosphorylase. It was subsequently determined that the enzyme’s function is to degrade RNA, not synthesize it; under test-tube conditions, however, it runs its natural reaction in reverse. The enzyme has been singularly valuable in enabling scientists to understand and re-create the process whereby the hereditary information contained in genes is translated, through RNA intermediaries, into enzymes that determine the functions and character of each cell.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#903 2021-05-09 00:10:27

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 48,424

Re: crème de la crème

869) Donald A. Glaser

Donald A. Glaser, in full Donald Arthur Glaser, (born September 21, 1926, Cleveland, Ohio, U.S.—died February 28, 2013, Berkeley, California), American physicist and recipient of the 1960 Nobel Prize for Physics for his invention (1952) and development of the bubble chamber, a research instrument used in high-energy physics laboratories to observe the behaviour of subatomic particles.

After graduating from Case Institute of Technology, Cleveland, in 1946, Glaser attended the California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, where he received a Ph.D. in physics and mathematics in 1950. He then began teaching at the University of Michigan, where he became a professor in 1957.

Glaser conducted research with Nobelist Carl Anderson, who was using cloud chambers to study cosmic rays. Glaser, recognizing that cloud chambers had a number of limitations, created a bubble chamber to learn about the pathways of subatomic particles. Because of the relatively high density of the bubble-chamber liquid (as opposed to the vapour that filled cloud chambers), collisions producing rare reactions were more frequent and were observable in finer detail. New collisions could be recorded every few seconds when the chamber was exposed to bursts of high-speed particles from particle accelerators. As a result, physicists were able to discover the existence of a host of new particles, notably quarks. At the age of 34, Glaser became one of the youngest scientists ever to be awarded a Nobel Prize.

In 1959 Glaser joined the staff of the University of California, Berkeley, where he became a professor of physics and molecular biology in 1964. In 1971 he cofounded the Cetus Corp., a biotechnology company that developed interleukin-2 and interferon for cancer therapy. The firm was sold (1991) to Chiron Corp., which was later acquired by Novartis. In the 1980s Glaser turned to the field of neurobiology and conducted experiments on vision and how it is processed by the human brain.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#904 2021-05-10 01:21:59

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 48,424

Re: crème de la crème

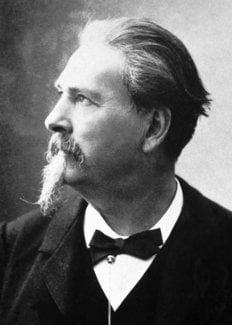

870) Bjørnstjerne Martinius Bjørnson

Bjørnstjerne Martinius Bjørnson, (born December 8, 1832, Kvikne, Norway—died April 26, 1910, Paris, France), poet, dramatist, novelist, journalist, editor, public speaker, theatre director, and one of the most prominent public figures in the Norway of his day. He was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1903 and is generally known, together with Henrik Ibsen, Alexander Kielland, and Jonas Lie, as one of “the four great ones” of 19th-century Norwegian literature. His poem “Ja, vi elsker dette landet” (“Yes, We Love This Land”) is the Norwegian national anthem.

Bjørnson, the son of a pastor, grew up in the small farming community of Romsdalen, which later became the scene of his country novels. From the start his writing was marked by clearly didactic intent; he sought to stimulate national pride in Norway’s history and achievements and to present ideals. For the first 15 years of his literary career he drew his inspiration from the sagas and from his knowledge of contemporary rural Norway. He exploited these two fields in what he described as his system of “crop rotation”: saga material was turned into plays, contemporary material into novels or peasant tales. Both stressed those links that bound the new Norway to the old; both served to raise the nation’s morale. The early products of this system were the peasant tale Synnøve solbakken (1857; Trust and Trial, Love and Life in Norway, and Sunny Hill), the one-act historical play Mellem slagene (1857; “Between the Battles”), and the tales Arne (1858) and En glad gut (1860; The Happy Boy) and the play Halte-Hulda (1858; “Lame Hulda”).

In 1857–59 he was Ibsen’s successor as artistic director at the Bergen Theatre. He married the actress Karoline Reimers in 1858 and also became the editor of the Bergenposten. Partly because of his activity with this paper, the Conservative representatives were defeated in 1859 and the path was cleared for the formation of the Liberal Party a short time later. After traveling abroad for three years, Bjørnson became director of the Christiania Theatre, and, from 1866 to 1871, he edited the Norsk Folkeblad. During this same time there also appeared the first edition of his Digte og sange (1870; Poems and Songs) and the epic poem Arnljot Gelline (1870).

Bjørnson’s political battles and literary feuds took up so much of his time that he left Norway in order to write. The two dramas that brought him an international reputation were thus written in self-imposed exile: En fallit (1875; The Bankrupt) and Redaktøren (1875; The Editor). Both fulfilled the then current demand on literature (stipulated by the Danish writer and critic Georg Brandes) to debate problems, as did the two dramas that followed: Kongen (1877; The King) and Det ny system (1879; The New System). Of his later works, two novels are remembered, Det flager i byen og på havnen (1884; The Heritage of the Kurts) and På Guds veje (1889; In God’s Way), as are a number of impressive dramas, including Over Ævne I og II (1883 and 1895; Beyond Our Power and Beyond Human Might). The first of the novels deals critically with Christianity and attacks the belief in miracles, whereas the second deals with social change and suggests that such change must begin in the schools. Paul Lange og Tora Parsberg (1898) is concerned with the theme of political intolerance.

Later in life, Bjørnson came to think of himself as a Socialist, working tirelessly in behalf of peace and international understanding. Bjørnson enjoyed worldwide fame, his plays were influential in establishing social realism in Europe, and he was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1903. Nonetheless, his international reputation has diminished in comparison with that of Ibsen.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#905 2021-05-12 00:15:37

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 48,424

Re: crème de la crème

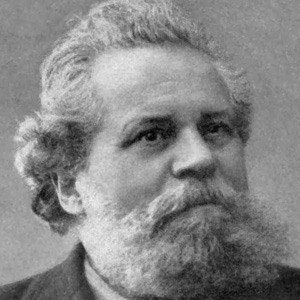

871) Frédéric Mistral

Frédéric Mistral, (born Sept. 8, 1830, Maillane, France—died March 25, 1914, Maillane), poet who led the 19th-century revival of Occitan (Provençal) language and literature. He shared the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1904 (with José Echegaray y Eizaguirre) for his contributions in literature and philology.

Mistral’s father was a well-to-do farmer in the former French province of Provence. He attended the Royal College of Avignon (later renamed the Frédéric Mistral School). One of his teachers was Joseph Roumanille, who had begun writing poems in the vernacular of Provence and who became his lifelong friend. Mistral took a degree in law at the University of Aix-en-Provence in 1851.

Wealthy enough to live without following a profession, he early decided to devote himself to the rehabilitation of Provençal life and language. In 1854, with several friends, he founded the Félibrige, an association for the maintenance of the Provençal language and customs, extended later to include the whole of southern France (le pays de la langue d’oc, “the country of the language of oc,” so called because the Provençal language uses oc for “yes,” in contrast to the French oui). As the language of the troubadours, Provençal had been the cultured speech of southern France and was used also by poets in Italy and Spain. Mistral threw himself into the literary revival of Provençal and was the guiding spirit and chief organizer of the Félibrige until his death in 1914.

Mistral devoted 20 years’ work to a scholarly dictionary of Provençal, entitled Lou Tresor dóu Félibrige, 2 vol. (1878). He also founded a Provençal ethnographic museum in Arles, using his Nobel Prize money to assist it. His attempts to restore the Provençal language to its ancient position did not succeed, but his poetic genius gave it some enduring masterpieces, and he is considered one of the greatest poets of France.

His literary output consists of four long narrative poems: Mirèio (1859; Mireio: A Provencal Poem), Calendau (1867), Nerto (1884), and Lou Pouèmo dóu Rose (1897; Eng. trans. The Song of the Rhône); a historical tragedy, La Reino Jano (1890; “Queen Jane”); two volumes of lyrics, Lis Isclo d’or (1876; definitive edition 1889) and Lis Oulivado (1912); and many short stories, collected in Prose d’Armana, 3 vol. (1926–29).

Mistral’s volume of memoirs, Moun espelido (Mes origines, 1906; Eng. trans. Memoirs of Mistral), is his best-known work, but his claim to greatness rests on his first and last long poems, Mirèio and Lou Pouèmo dóu Rose, both full-scale epics in 12 cantos.

Mirèio, which is set in the poet’s own time and district, is the story of a rich farmer’s daughter whose love for a poor basketmaker’s son is thwarted by her parents and ends with her death in the Church of Les Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer. Into this poem Mistral poured his love for the countryside where he was born. Mirèio skillfully combines narration, dialogue, description, and lyricism and is notable for the springy, musical quality of its highly individual stanzaic form. Under its French title, Mireille, it inspired an opera by Charles Gounod (1863).

Lou Pouèmo dóu Rose tells of a voyage on the Rhône River from Lyon to Beaucaire by the barge Lou Caburle, which is boarded first by a romantic young prince of Holland and later by the daughter of a poor ferryman. The romance between them is cut short by disaster when the first steamboat to sail on the Rhône accidentally sinks Lou Caburle. Though the crew swims ashore, the lovers are drowned. Although less musical and more dense in style than Mirèio, this epic is as full of life and colour. It suggests that Mistral, late in life, realized that his aim had not been reached and that much of what he loved was, like his heroes, doomed to perish.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#906 2021-05-13 00:32:31

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 48,424

Re: crème de la crème

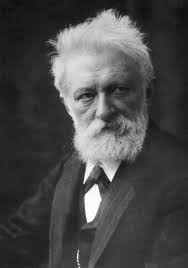

872) Giosuè Carducci

Giosuè Carducci, (born July 27, 1835, Val di Castello, near Lucca, Tuscany [now Italy]—died Feb. 16, 1907, Bologna, Italy), Italian poet, winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1906, and one of the most influential literary figures of his age.

The son of a republican country doctor, Carducci spent his childhood in the wild Maremma region of southern Tuscany. He studied at the University of Pisa and in 1860 became professor of Italian literature at Bologna, where he lectured for more than 40 years. He was made a senator for life in 1890 and was revered by the Italians as a national poet.

In his youth Carducci was the centre of a group of young men determined to overthrow the prevailing Romanticism and to return to classical models. Giuseppe Parini, Vincenzo Monti, and Ugo Foscolo were his masters, and their influence is evident in his first books of poems (Rime, 1857; later collected in Juvenilia [1880] and Levia gravia [1868; “Light and Serious Poems”]). He showed both his great power as a poet and the strength of his republican, anticlerical feeling in his hymn to Satan, “Inno a Satana” (1863), and in his Giambi ed epodi (1867–69; “Iambics and Epodes”), inspired chiefly by contemporary politics. Its violent, bitter language reflects the virile, rebellious character of the poet.

Rime nuove (1887; The New Lyrics) and Odi barbare (1877; The Barbarian Odes) contain the best of Carducci’s poetry: the evocations of the Maremma landscape and the memories of childhood; the lament for the loss of his only son; the representation of great historical events; and the ambitious attempts to recall the glory of Roman history and the pagan happiness of classical civilization. Carducci’s enthusiasm for the classical in art led him to adapt Latin prosody to Italian verse, and his Odi barbare are written in metres imitative of Horace and Virgil. His research in Italian literature was warmed by his poetic imagination and style, and his best prose works equal his poetry.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#907 2021-05-15 00:08:49

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 48,424

Re: crème de la crème

873) Rudolf Christoph Eucken

Rudolf Christoph Eucken, (born Jan. 5, 1846, Aurich, East Friesland [now in Germany]—died Sept. 14, 1926, Jena, Ger.), German Idealist philosopher, winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature (1908), interpreter of Aristotle, and author of works in ethics and religion.

Eucken studied at the University of Göttingen under the German thinker Rudolf Hermann Lotze, a teleological Idealist, and at Berlin under Friedrich Adolf Trendelenburg, a German philosopher whose ethical concerns and historical treatment of philosophy attracted him. Appointed professor of philosophy at the University of Basel, Switz., in 1871, Eucken left in 1874 to become professor of philosophy at the University of Jena, a position he held until 1920.

Distrusting abstract intellectualism and systematics, Eucken centred his philosophy upon actual human experience. He maintained that man is the meeting place of nature and spirit and that it is his duty and his privilege to overcome his nonspiritual nature by incessant active striving after the spiritual life. This pursuit, sometimes termed ethical activism, involves all of man’s faculties but especially requires efforts of the will and intuition.

A strident critic of naturalist philosophy, Eucken held that man’s soul differentiated him from the rest of the natural world and that the soul could not be explained only by reference to natural processes. His criticisms are particularly evident in Individual and Society (1923) and Der Sozialismus und seine Lebensgestaltung (1920; Socialism: An Analysis, 1921). The second work attacked Socialism as a system that limits human freedom and denigrates spiritual and cultural aspects of life.

Eucken’s Nobel Prize diploma referred to the “warmth and strength in presentation with which in his numerous works he has vindicated and developed an idealist philosophy of life.” His other works include Der Sinn und Wert des Lebens (1908; The Meaning and Value of Life, 1909) and Können wir noch Christen sein? (1911; Can We Still Be Christians?, 1914).

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#908 2021-05-17 00:36:18

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 48,424

Re: crème de la crème

874) Selma Lagerlöf

Selma Lagerlöf, in full Selma Ottiliana Lovisa Lagerlöf, (born Nov. 20, 1858, Mårbacka, Sweden—died March 16, 1940, Mårbacka), novelist who in 1909 became the first woman and also the first Swedish writer to win the Nobel Prize for Literature.

An illness left her lame for a time, but otherwise her childhood was happy. She was taught at home, then trained in Stockholm as a teacher, and in 1885 went to Landskrona as schoolmistress. There she wrote her first novel, Gösta Berlings saga, 2 vol. (1891). A chronicle of life in the heyday of her native Värmland’s history, the age of prosperous iron founders and small manors, the book recounts the story of the 12 Cavaliers, led by Gösta Berling, a renegade priest of weak character but irresistible charm. Written in a lyrical style, full of pathos, it showed the influence of Thomas Carlyle and played a part in the Swedish Romantic revival of the 1890s.

In 1894 she published a collection of stories, Osynliga länkar (Invisible Links), and in 1895 she won a traveling scholarship, gave up teaching, and devoted herself to writing. After visiting Italy she published Antikrists mirakler (1897; The Miracles of Antichrist), a socialist novel about Sicily. Another collection, En herrgårdssägen (Tales of a Manor), is one of her finest works. A winter in Egypt and Palestine (1899–1900) inspired Jerusalem, 2 vol. (1901–02), which established her as the foremost Swedish novelist. Other notable works were Herr Arnes Penningar (1904), a tersely but powerfully told historical tale; and Nils Holgerssons underbara resa genom Sverige, 2 vol. (1906–07; The Wonderful Adventures of Nils and Further Adventures of Nils), a geography reader for children.

World War I disturbed her deeply, and for some years she wrote little. Then, in Mårbacka (1922), Ett barns memoarer (1930; Memories of My Childhood), and Dagbok för Selma Lagerlöf (1932; The Diary of Selma Lagerlöf ), she recalled her childhood with subtle artistry and also produced a Värmland trilogy: Löwensköldska ringen (1925; The Ring of the Löwenskölds), set in the 18th century; Charlotte Löwensköld (1925); and Anna Svärd (1928). She was deeply attached to the family manor house at Mårbacka, which had been sold after her father’s death but which she bought back with her Nobel Prize money. Selma Lagerlöf ranks among the most naturally gifted of modern storytellers.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#909 2021-05-19 00:24:20

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 48,424

Re: crème de la crème

875) Paul Johann Ludwig von Heyse

Paul Johann Ludwig von Heyse, (born March 15, 1830, Berlin, Prussia [Germany]—died April 2, 1914, Munich, Ger.), German writer and prominent member of the traditionalist Munich school who received the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1910.

Heyse studied classical and Romance languages and traveled for a year in Italy, supported by a research grant. After completing his studies he became an independent scholar and was called to Munich by Maximilian II of Bavaria. There, with the poet Emanuel Geibel, he became the head of the Munich circle of writers, who sought to preserve traditional artistic values from the encroachments of political radicalism, materialism, and realism. He became a master of the carefully wrought short story, a chief example of which is L’Arrabbiata (1855). He also published novels (Kinder der Welt, 1873; Children of the World) and many unsuccessful plays. Among his best works are his translations of the works of Giacomo Leopardi and other Italian poets. His poems provided the lyrics for many lieder by the composer Hugo Wolf. Heyse, who was given to idealization and who refused to portray the dark side of life, became an embittered opponent of the growing school of Naturalism, and his popularity had greatly decreased by the time he received the Nobel Prize.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#910 2021-05-21 00:08:35

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 48,424

Re: crème de la crème

876) Maurice Maeterlinck

Maurice Maeterlinck, in full Maurice Polydore-Marie-Bernard Maeterlinck, also called (from 1932) Comte Maeterlinck, (born August 29, 1862, Ghent, Belgium—died May 6, 1949, Nice, France), Belgian Symbolist poet, playwright, and essayist who won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1911 for his outstanding works of the Symbolist theatre. He wrote in French and looked mainly to French literary movements for inspiration.

Maeterlinck studied law at the University of Ghent and was admitted to the bar in that city in 1886. In Paris in 1885–86 he met Auguste Villiers de L’Isle-Adam and the leaders of the Symbolist movement, and he soon abandoned law for literature. His first verse collection, Serres chaudes (“Hothouses”), and his first play, La Princesse Maleine, were published in 1889. Maeterlinck made a dramatic breakthrough in 1890 with two one-act plays, L’Intruse (The Intruder) and Les Aveugles (The Blind). His Pelléas et Mélisande (1892), produced in Paris at the avant-garde Théâtre de l’Oeuvre by the director Aurélien Lugné-Poë, is the unquestioned masterpiece of Symbolist drama and provided the basis for an opera (1902) by Claude Debussy. Set in a nebulous, fairy-tale past, the play conveys a mood of hopeless melancholy and doom in its story of the destructive passion of Princess Mélisande, who falls in love with her husband’s younger brother, Pelléas. Though written in prose, Pelléas et Mélisande may be considered the most accomplished of all 19th-century attempts at poetic drama.

Maeterlinck wrote many other plays, including historical dramas such as Monna Vanna (1902). Gradually, his Symbolism was tempered by his interest in English drama, especially William Shakespeare and the Jacobeans. Only L’Oiseau bleu (1908; The Blue Bird) rivaled Pelléas et Mélisande in popularity. An allegorical fantasy conceived as a play for children, it portrays a search for happiness in the world. First performed by the Moscow Art Theatre in 1908, this somewhat sentimental dramatic parable was highly regarded for a time, but its charm has evaporated, and the optimism of the play now seems facile. After he won the Nobel Prize, however, his reputation declined, although his Le Bourgmestre de Stilmonde (1917; The Burgomaster of Stilmonde), a patriotic play in which he explores the problems of Flanders under the wartime rule of an unprincipled German officer, briefly enjoyed great success.

In his Symbolist plays, Maeterlinck uses poetic speech, gesture, lighting, setting, and ritual to create images that reflect his protagonists’ moods and dilemmas. Often the protagonists are waiting for something mysterious and fearful that will destroy them. The profound and moving atmosphere of the plays, though lacking in intellectual complexity, is augmented by tentative dialogue, based on half-formed suggestions, at times naively repetitious, and occasionally sentimental, but sometimes possessed of great subtlety and power. As a dramatist, Maeterlinck influenced Hugo von Hofmannsthal, W.B. Yeats, John Millington Synge, and Eugene O’Neill. Maeterlinck’s plays have been widely translated, and no Belgian dramatist had greater effect on worldwide audiences.

Maeterlinck’s prose writings are remarkable blends of mysticism, occultism, and interest in the world of nature. They represent the common Symbolist reaction against materialism, science, and mechanization and are concerned with such questions as the immortality of the soul, the nature of death, and the attainment of wisdom. Maeterlinck presented his mystical speculations in Le Trésor des humbles (1896; The Treasure of the Humble) and La Sagesse et la destinée (1898; “Wisdom and Destiny”). His most widely read prose writings, however, are two extended essays, La Vie des abeilles (1901; The Life of the Bee) and L’Intelligence des fleurs (1907; The Intelligence of Flowers), in which Maeterlinck sets out his philosophy of the human condition. Maeterlinck was made a count by the Belgian king in 1932.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#911 2021-05-23 00:07:08

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 48,424

Re: crème de la crème

877) Gerhart Hauptmann

Gerhart Hauptmann, in full Gerhart Johann Robert Hauptmann, (born November 15, 1862, Bad Salzbrunn, Silesia, Prussia [now Szczawno-Zdrój, Poland]—died June 6, 1946, Agnetendorf, Germany [now Jagniątków, Poland]), German playwright, poet, and novelist who was a recipient of the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1912.

Hauptmann was born in a then-fashionable Silesian resort town, where his father owned the main hotel. He studied sculpture from 1880 to 1882 at the Breslau Art Institute and then studied science and philosophy at the university in Jena (1882–83). He worked as a sculptor in Rome (1883–84) and studied further in Berlin (1884–85). It was at this time that he decided to make his career as a poet and dramatist. Having married the well-to-do Marie Thienemann in 1885, Hauptmann settled down in Erkner, a suburb of Berlin, taking lessons in acting and associating with a group of scientists, philosophers, and avant-garde writers who were interested in naturalist and socialist ideas. Hauptmann began writing novellas, most notably Fasching (1887; “Carnival”), but his membership in the literary club Durch (“Through”) and his reading of the works of such writers as Émile Zola and Ivan Turgenev led him to start writing plays.

In October 1889 the performance of Hauptmann’s social drama Vor Sonnenaufgang (Before Dawn) made him famous overnight, though it shocked the theatregoing public. This starkly realistic tragedy, dealing with contemporary social problems, signaled the end of the rhetorical and highly stylized German drama of the 19th century. Encouraged by the controversy, Hauptmann wrote in rapid succession a number of outstanding dramas on naturalistic themes (heredity, the plight of the poor, the clash of personal needs with societal restrictions) in which he artistically reproduced social reality and common speech. Most gripping and humane, as well as most objectionable to the political authorities at the time of its publication, is Die Weber (1892; The Weavers), a compassionate dramatization of the Silesian weavers’ revolt of 1844. Das Friedensfest (1890; “The Peace Festival”) is an analysis of the troubled relations within a neurotic family, while Einsame Menschen (1891; Lonely Lives) describes the tragic end of an unhappy intellectual torn between his wife and a young woman (patterned after the writer Lou Andreas-Salomé) with whom he can share his thoughts.

Hauptmann resumed his treatment of proletarian tragedy with Fuhrmann Henschel (1898; Drayman Henschel), a claustrophobic study of a workman’s personal deterioration from the stresses of his domestic life. However, critics felt that the playwright had abandoned naturalistic tenets in Hanneles Himmelfahrt (1894; The Assumption of Hannele), a poetic evocation of the dreams an abused workhouse girl has shortly before she dies. Der Biberpelz (1893; The Beaver Coat) is a successful comedy, written in a Berlin dialect, that centres on a cunning female thief and her successful confrontation with pompous, stupid Prussian officials.

Hauptmann’s longtime estrangement from his wife resulted in their divorce in 1904, and in the same year he married the violinist Margarete Marschalk, with whom he had moved in 1901 to a house in Agnetendorf in Silesia. Hauptmann spent the rest of his life there, though he traveled frequently.

Although Hauptmann helped to establish naturalism in Germany, he later abandoned naturalistic principles in his plays. In his later plays, fairy-tale and saga elements mingle with mystical religiosity and mythical symbolism. The portrayal of the primordial forces of the human personality in a historical setting (Kaiser Karls Geisel, 1908; Charlemagne’s Hostage) stands beside naturalistic studies of the destinies of contemporary people (Dorothea Angermann, 1926). The culmination of the final phase in Hauptmann’s dramatic work is the Atrides cycle, Die Atriden-Tetralogie (1941–48), which expresses through tragic Greek myths Hauptmann’s horror of the cruelty of his own time.

Hauptmann’s stories, novels, and epic poems are as varied as his dramatic works and are often thematically interwoven with them. The novel Der Narr in Christo, Emanuel Quint (1910; The Fool in Christ, Emanuel Quint) depicts, in a modern parallel to the life of Christ, the passion of a Silesian carpenter’s son, possessed by pietistic ecstasy. A contrasted figure is the apostate priest in his most famous story, Der Ketzer von Soana (1918; The Heretic of Soana), who surrenders himself to a pagan cult of Eros.

In his early career Hauptmann found sustained effort difficult; later his literary production became more prolific, but it also became more uneven in quality. For example, the ambitious and visionary epic poems Till Eulenspiegel (1928) and Der grosse Traum (1942; “The Great Dream”) successfully synthesize his scholarly pursuits with his philosophical and religious thinking, but are of uncertain literary value. The cosmological speculations of Hauptmann’s later decades distracted him from his spontaneous talent for creating characters that come alive on the stage and in the imagination of the reader. Nevertheless, Hauptmann’s literary reputation in Germany was unequaled until the ascendancy of Nazism, when he was barely tolerated by the regime and at the same time was denounced by émigrés for staying in Germany. Though privately out of tune with the Nazi ideology, he was politically naive and tended to be indecisive. He remained in Germany throughout World War II and died a year after his Silesian environs had been occupied by the Soviet Red Army.

Hauptmann was the most prominent German dramatist of the early 20th century. The unifying element of his vast and varied literary output is his sympathetic concern for human suffering, as expressed through characters who are generally passive victims of social and other elementary forces. His plays, the early naturalistic ones especially, are still frequently performed.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#912 2021-05-25 00:06:52

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 48,424

Re: crème de la crème

878) Romain Rolland

Romain Rolland, (born Jan. 29, 1866, Clamecy, France—died Dec. 30, 1944, Vézelay), French novelist, dramatist, and essayist, an idealist who was deeply involved with pacifism, the fight against fascism, the search for world peace, and the analysis of artistic genius. He was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1915.

At age 14, Rolland went to Paris to study and found a society in spiritual disarray. He was admitted to the École Normale Supérieure, lost his religious faith, discovered the writings of Benedict de Spinoza and Leo Tolstoy, and developed a passion for music. He studied history (1889) and received a doctorate in art (1895), after which he went on a two-year mission to Italy at the École Française de Rome. At first, Rolland wrote plays but was unsuccessful in his attempts to reach a vast audience and to rekindle “the heroism and the faith of the nation.” He collected his plays in two cycles: Les Tragédies de la foi (1913; “The Tragedies of Faith”), which contains Aërt (1898), and Le Théâtre de la révolution (1904), which includes a presentation of the Dreyfus Affair, Les Loups (1898; The Wolves), and Danton (1900).

In 1912, after a brief career in teaching art and musicology, he resigned to devote all his time to writing. He collaborated with Charles Péguy in the journal Les Cahiers de la Quinzaine, where he first published his best-known novel, Jean-Christophe, 10 vol. (1904–12). For this and for his pamphlet Au-dessus de la mêlée (1915; “Above the Battle”), a call for France and Germany to respect truth and humanity throughout their struggle in World War I, he was awarded the Nobel Prize. His thought was the centre of a violent controversy and was not fully understood until 1952 with the posthumous publication of his Journal des années de guerre, 1914–1919 (“Journal of the War Years, 1914–1919”). In 1914 he moved to Switzerland, where he lived until his return to France in 1937.

His passion for the heroic found expression in a series of biographies of geniuses: Vie de Beethoven (1903; Beethoven), who was for Rolland the universal musician above all the others; Vie de Michel-Ange (1905; The Life of Michel Angelo), and Vie de Tolstoi (1911; Tolstoy), among others.

Rolland’s masterpiece, Jean-Christophe, is one of the longest great novels ever written and is a prime example of the roman fleuve (“novel cycle”) in France. An epic in construction and style, rich in poetic feeling, it presents the successive crises confronting a creative genius—here a musical composer of German birth, Jean-Christophe Krafft, modeled half after Beethoven and half after Rolland—who, despite discouragement and the stresses of his own turbulent personality, is inspired by love of life. The friendship between this young German and a young Frenchman symbolizes the “harmony of opposites” that Rolland believed could eventually be established between nations throughout the world.

After a burlesque fantasy, Colas Breugnon (1919), Rolland published a second novel cycle, L’Âme-enchantée, 7 vol. (1922–33), in which he exposed the cruel effects of political sectarianism. In the 1920s he turned to Asia, especially India, seeking to interpret its mystical philosophy to the West in such works as Mahatma Gandhi (1924). Rolland’s vast correspondence with such figures as Albert Schweitzer, Albert Einstein, Bertrand Russell, and Rabindranath Tagore was published in the Cahiers Romain Rolland (1948). His posthumously published Mémoires (1956) and private journals bear witness to the exceptional integrity of a writer dominated by the love of mankind.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#913 2021-05-27 00:13:18

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 48,424

Re: crème de la crème

879) Verner von Heidenstam

Verner von Heidenstam, in full Carl Gustaf Verner von Heidenstam, (born July 6, 1859, Olshammar, Sweden—died May 20, 1940, Övralid), poet and prose writer who led the literary reaction to the Naturalist movement in Sweden, calling for a renaissance of the literature of fantasy, beauty, and national themes. He won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1916.

Ill health forced Heidenstam to spend most of his youth in the central and eastern Mediterranean countries. His first book of poems, Vallfart och vandringsår (1888; “Pilgrimage and Wander Years”), full of the fables of the southern lands and the philosophy of the East, was an immediate success with the Swedish public. With his essay “Renässans” (1889) he first voiced his opposition to naturalism and the realistic literary program in Sweden.

His efforts toward the realization of a new Swedish literature include two volumes of poems, Dikter (1895) and his last volume, Nya dikter (1915), many poems of which are translated in Sweden’s Laureate: Selected Poems of Verner von Heidenstam (1919). He also wrote several volumes of historical fiction, the most important of which are Karolinerna, 2 vol. (1897–98; The Charles Men), and Folkungaträdet (1905–07; The Tree of the Folkungs). After the turn of the century Heidenstam’s works lost their popular appeal, and he wrote virtually nothing during the last 25 years of his life.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#914 2021-05-29 00:08:00

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 48,424

Re: crème de la crème

880) Karl Adolph Gjellerup

Karl Adolph Gjellerup, (born June 2, 1857, Roholte, Den.—died Oct. 11, 1919, Klotzsche, Ger.), Danish poet and novelist who shared the 1917 Nobel Prize for Literature with his compatriot Henrik Pontoppidan.

The son of a parson, Gjellerup studied theology, although, after coming under the influence of Darwinism and the new radical ideas of the critic Georg Brandes, he thought of himself as an atheist. This atheism, which turned out to be no more than a break with Christianity, was proclaimed in his first book En Idealist Shildring af Epigonus (1878; “An Idealist, A Description of Epigonus”) and in his farewell to theology, Germanernes lærling (1882; “The Teutons’ Apprentice”). The latter, however, indicated the path that was to take him, via German idealist philosophy and Romanticism, back to a conscious search for religion, which finally found its satisfaction in his preoccupation with Buddhism and other Oriental religions. This last period is represented by two books: Minna (1889), a novel of contemporary Germany, where Gjellerup lived in his later years, and Pilgrimen Kamanita (1906; The Pilgrim Kamanita), an exotic tale of reincarnation set in India.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#915 2021-05-31 00:28:29

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 48,424

Re: crème de la crème

881) Henrik Pontoppidan

Henrik Pontoppidan, (born July 24, 1857, Fredericia, Denmark—died August 21, 1943, Ordrup, near Copenhagen), Realist writer who shared with Karl Gjellerup the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1917 for “his authentic descriptions of present-day life in Denmark.” Pontoppidan’s novels and short stories—informed with a desire for social progress but despairing, later in his life, of its realization—present an unusually comprehensive picture of his country and his epoch.

The son of a clergyman, Pontoppidan partly revolted against his environment by beginning studies in engineering in Copenhagen in 1873. In 1879 he broke off his studies and became for several years a teacher. His first collection of stories, Stækkede Vinger (“Clipped Wings”), was published in 1881, and thereafter he supported himself by writing, until 1900 partly as a journalist with various Copenhagen papers.

Pontoppidan’s output—mainly novels and short stories written in an emotionally detached, epic style—stretches over half a century and covers most aspects of Danish life. It is usually characterized by a blend of social criticism and aristocratic disillusionment and is expressive of a pessimistic irony.

His first books were about country-town life. Landsbybilleder (1883; “Village Pictures”), Fra Hytterne (1887; “From the Cottages”), and Skyer (1890; “Clouds”) are all characterized by social indignation, though also by ironic appreciation of the complacency and passivity of country people. The long novel Det Forjættede Land, 3 vol. (1891–95; The Promised Land), describes the religious controversies in country districts. In the 1890s Pontoppidan wrote short novels on psychological, aesthetic, and moral problems—for example, Nattevagt (1894; “Night Watch”), Den Gamle Adam (1895; “The Old Adam”), and Højsang (1896; “Song of Songs”). These were followed by a major work, the novel Lykke-Per (1898–1904; Lucky Per, originally published in eight volumes), in which the chief character bears some resemblance to Pontoppidan himself. He is a clergyman’s son who rebels against the puritanical atmosphere of his home and seeks his fortune in the capital as an engineer. The novel’s theme is the power of environment, and national tendencies toward daydreaming and fear of reality are condemned.

Pontoppidan’s great novel De dødes rige, 5 vol. (1912–16; “The Realm of the Dead”), shows his dissatisfaction with political developments after the liberal victory of 1901 and with the barrenness of the new era. His final novel, Mands Himmerig (1927; “Man’s Heaven”), describes neutral Denmark during World War I and attacks carefree materialism. His last important work was the four volumes of memoirs that he published between 1933 and 1940 and that appeared in a collected and abridged version, entitled Undervejs til mig selv (1943; “On the Way to Myself”).

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#916 2021-06-02 00:24:28

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 48,424

Re: crème de la crème

882) Carl Friedrich Georg Spitteler

Swiss poet Carl Friedrich Georg Spitteler (24 April 1845 – 29 December 1924) received the 1919 Nobel Prize for Literature to honor his many contributions to poetry, most notably the mammoth Olympian Spring (revised in 1910), which many critics regard as his masterpiece. The epic work details the rise of new gods to power and consciousness. Spitteler was also known by the pseudonym Carl Felix Tandem. His best–known works are Prometheus und Epimethus, Gustav, Lachende Wahrheiten, (Laughing Games), and Olympischer Fruehling (Olympic Spring), in which the poet's own metrical scheme impressed critics.

Early Life

Born in the small town of Liestal (Baselland Canton), Switzerland on April 24, 1845, Spitteler moved with his family to the Swiss city of Bern when he was four. His father served there as appointed treasurer of the new Swiss Confederacy, but the Spittelers returned to Liestal when his term ended in 1856. The young Spitteler attended school (gymnasium) in Basle while living with his aunt, and then returned to Liestal and traveled by train daily to attend classes at the Pädagogium (the Swiss equivalent of high school). There, in 1862, he began to develop his love of literature. In his autobiography, he recalled having the sudden realization, "like lightening," that poetry was the ideal way for him to express his defiance and true thoughts. He decided that he would make his living as a poet, little knowing the challenges.

After finishing his requirements at the Pädagogium, Spitteler unhappily honored his father's request that he study law, and in 1863 enrolled at the University of Switzerland for that purpose. He did not like law, however, and in 1864 he left the school without permission for Lucerne, Switzerland, to think about his professional path. Despite his reluctance, the poet completed a law degree in 1865, and then studied theology until 1870 at schools in Basle, Heidelberg, Germany; and Zürich. (His first attempt at earning a degree in 1869 failed). Spitteler's contempt for Christianity and other major organized religions seemed to spark his interest in theology, and some biographies suggest his intense study might have been to arm himself with arguments against such beliefs. Spitteler, meanwhile, continued to write during his spare time, experimenting with different styles and techniques.

Published First Work

After completing his theology degree, Spitteler rejected an invitation to start a career as a Protestant minister, instead accepting a job tutoring the children of a Russian general in St. Petersburg. He worked there from 1871 to 1879, spending some of the time in Finland with the family. During this period, his love of writing intensified. He wrote Prometheus and Epimetheus, publishing the work with his own funds after returning to Switzerland in 1881 and using the pseudonym Carl Felix Tandem. He contrasted dogmas with ideals and convention with individualism in this epic poem, but the public and critics alike ignored the volume. He could not know that pioneer psychologist Carl Jung would eventually formulate his "introvert" and "extrovert" personality types based on the main characters of Spitteler's work.

At 36, Spitteler became disheartened by his perceived failure as a poet, and vowed to dismiss writing as a profession. He also missed what he described as the warmth, good will, and open–mindedness of the Russians, and complained that his own countrymen were homogenous, brusque, and oppressive, rebuffing anyone who behaved abnormally.

Spitteler fell back on teaching to support himself, working from 1881 to 1885 in Neuveville, Switzerland and then as a newspaper reporter for the Basle Grenzpost from 1885 to 1886 and the Neue Zürcher Zeitung (New Inhabitant of Zurich) from 1890 to 1892. Meanwhile, he had married one of his former Neueville students, Marie op der Hoff, in 1883. He continued to write when he could, however, and published the poems Extramundana and Schmetterlinge (Butterflies) in 1883 and 1889, respectively. Spitteler received an unexpected boost in his popularity in 1887 when German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche recommended the poet's works to the editor of Kunswart, a small periodical publication in Munich, Germany.

Spitteler's life changed dramatically in 1892 when his wife's parents died. They left her a generous inheritance, which enabled the couple to move to Lucerne and gave Spitteler the chance to write full–time without worrying about making a living. With the pressure off and all the time he needed, the poet wrote feverishly to make up for all the time he had lost. He published Gustav later that year.

Critics still consider Olympian Spring Spitteler's best and most important work. He published the epic in four volumes from 1900 to 1906: "Overture," "Hera the Bride," "High Tide," and "End and Change." Spitteler revised the work in 1910. A medley of fantasy, religion, and mythology, the allegory is written in iambic hexameter and explores such universal concerns as faith, morality, hope, despair, and ethics in a setting among the Greek gods.

Spitteler, however, had to wait until after the second installment was published before he received any recognition for the work outside his homeland. This came suddenly when renowned musician Felix Weingartner distributed a pamphlet in Germany in 1904 lauding the poet's work and proclaiming him a genius. At last, Spitteler had the recognition he had craved for so long. Critics began comparing him to the seventeenth–century poet–priest John Milton and acclaimed the work as a masterpiece of creativity and originality. In 1908 he published Meine Beziehungen Zu Nietzsche (My Relationship to Nietzsche), which countered accusations that he had borrowed themes from the philosopher's popular 1891 book, Thus Spake Zarathustra to write his own Prometheus and Epimetheus.

After completing Olympian Spring, Spitteler continued to write, publishing the semiautobiographical novel Imago in 1906, which centers on the struggle between creative minds and middle–class values; Gerold und Hansli: Die Madchenfeinde (Two Little Misogynists) in 1907; and Meine Fruhesten Erlebnisse (My Earliest Experiences) in 1914.

Won Nobel Prize For Literature

Despite his controversial, vitriolic speeches urging Switzerland to maintain its legendary political neutrality and avoid siding with either Germany or France World War I commenced, the Nobel Prize Committee awarded Spitteler the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1919. He was 75 years old, however, and failing health prevented him from attending the ceremony in 1920.

Spitteler revised his original Prometheus und Epimetheus manuscript in 1924, making all the verses rhyme and publishing it as Prometheus der Dulder (Prometheus the Sufferer). He died shortly thereafter in Lucerne on December 24, 1924.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#917 2021-06-04 00:10:26

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 48,424

Re: crème de la crème

883) Knut Hamsun

Knut Hamsun, pseudonym of Knut Pedersen, (born August 4, 1859, Lom, Norway—died February 19, 1952, near Grimstad), Norwegian novelist, dramatist, poet, and winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1920. A leader of the Neoromantic revolt at the turn of the century, he rescued the novel from a tendency toward excessive naturalism.

Of peasant origin, Hamsun spent most of his childhood in remote Hamarøy, Nordland county, and had almost no formal education. He started to write at age 19, when he was a shoemaker’s apprentice in Bodø, in northern Norway. During the next 10 years, he worked as a casual labourer. Twice he visited the United States, where he held a variety of mostly menial jobs in Chicago, North Dakota, and Minneapolis, Minnesota.

His first publication was the novel Sult (1890; Hunger), the story of a starving young writer in Norway. Sult marked a clear departure from the social realism of the typical Norwegian novel of the period. Its refreshing viewpoint and impulsive, lyrical style had an electrifying effect on European writers. Hamsun followed his first success with a series of lectures that revealed his obsession with August Strindberg and attacked such idols as Henrik Ibsen and Leo Tolstoy, and he produced a flow of works that continued until his death.

Like the asocial heroes of his early works—e.g., Mysterier (1892; Mysteries), Pan (1894; Eng. trans. Pan), and Victoria (1898; Eng. trans. Victoria)—Hamsun either was indifferent to or took an irreverent view of progress. In a work of his mature style, Markens grøde (1917; Growth of the Soil), he expresses a back-to-nature philosophy. But his message of fierce individualism, influenced by Friedrich Nietzsche and Strindberg, remains constant. Consistent to the end in his antipathy to modern Anglo-American culture, Hamsun supported the Germans during their occupation of Norway in World War II. After the war he was imprisoned as a traitor, but charges against him were dropped in view of his age. He was, however, convicted of economic collaboration and had to pay a fine that ruined him financially.

Hamsun’s collaboration with the Nazis seriously damaged his reputation, but after his death critical interest in his works was renewed and new translations made them again accessible to an international readership. Already in 1949, at age 90, he had made a remarkable literary comeback with Paa gjengrodde stier (On Overgrown Paths), which was in part memoir, in part self-defense, but first and foremost a treasure trove of vibrant impressions of nature and the seasons. His deliberate irrationalism and his wayward, spontaneous, impressionistic style had wide influence throughout Europe, and such writers as Maxim Gorky, Thomas Mann, and Isaac Bashevis Singer acknowledged him as a master.

A six-volume comprehensive edition of Hamsun’s letters, Knut Hamsuns brev, was published in Norwegian (1994–2001), with two volumes of Selected Letters (1990–98) appearing in English translation.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#918 2021-06-06 00:09:57

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 48,424

Re: crème de la crème

884) Anatole France

Anatole France, pseudonym of Jacques-Anatole-François Thibault, (born April 16, 1844, Paris, France—died Oct. 12, 1924, Saint-Cyr-sur-Loire), writer and ironic, skeptical, and urbane critic who was considered in his day the ideal French man of letters. He was elected to the French Academy in 1896 and was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1921.

The son of a bookseller, he spent most of his life around books. At school he received the foundations of a solid humanist culture and decided to devote his life to literature. His first poems were influenced by the Parnassian revival of classical tradition, and, though scarcely original, they revealed a sensitive stylist who was already cynical about human institutions.

This ideological skepticism appeared in his early stories: Le Crime de Sylvestre Bonnard (1881), a novel about a philologist in love with his books and bewildered by everyday life; La Rôtisserie de la Reine Pédauque (1893; At the Sign of the Reine Pédauque), which discreetly mocks belief in the occult; and Les Opinions de Jérome Coignard (1893), in which an ironic and perspicacious critic examines the great institutions of the state. His personal life underwent considerable turmoil. His marriage in 1877 to Marie-Valérie Guérin de Sauville ended in divorce in 1893. He had met Madame Arman de Caillavet in 1888, and their liaison inspired his novels Thaïs (1890), a tale set in Egypt of a courtesan who becomes a saint, and Le Lys rouge (1894; The Red Lily), a love story set in Florence.

A marked change in France’s work first appears in four volumes collected under the title L’Histoire contemporaine (1897–1901). The first three volumes—L’Orme du mail (1897; The Elm-Tree on the Mall), Le Mannequin d’osier (1897; The Wicker Work Woman), and L’Anneau d’améthyste (1899; The Amethyst Ring)—depict the intrigues of a provincial town. The last volume, Monsieur Bergeret à Paris (1901; Monsieur Bergeret in Paris), concerns the participation of the hero, who had formerly held himself aloof from political strife, in the Alfred Dreyfus affair. This work is the story of Anatole France himself, who was diverted from his role of an armchair philosopher and detached observer of life by his commitment to support Dreyfus. After 1900 he introduced his social preoccupations into most of his stories. Crainquebille (1903), a comedy in three acts adapted by France from an earlier short story, dramatizes the unjust treatment of a small tradesman and proclaims the hostility toward the bourgeois order that led France eventually to embrace socialism. Toward the end of his life, his sympathies were drawn to communism. However, Les Dieux ont soif (1912; The Gods are Athirst) and L’Île des Pingouins (1908; Penguin Island) show little belief in the ultimate arrival of a fraternal society. World War I reinforced his profound pessimism and led him to seek refuge from his times in childhood reminiscences. Le Petit Pierre (1918; Little Pierre) and La Vie en fleur (1922; The Bloom of Life) complete the cycle started in Le Livre de mon ami (1885; My Friend’s Book).

France has been faulted for the thinness of his plots and for his lack of a vital creative imagination. His works are, however, considered remarkable for their wide-ranging erudition, their wit and irony, their passion for social justice, and their classical clarity, qualities that mark France as an heir to the tradition of Denis Diderot and Voltaire.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#919 2021-06-08 00:09:34

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 48,424

Re: crème de la crème

885) Jacinto Benavente y Martínez

Jacinto Benavente y Martínez, (born Aug. 12, 1866, Madrid, Spain—died July 14, 1954, Madrid), one of the foremost Spanish dramatists of the 20th century, who was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1922. He returned drama to reality by way of social criticism: declamatory verse giving way to prose, melodrama to comedy, formula to experience, impulsive action to dialogue and the play of minds. Benavente showed a preoccupation with aesthetics and later with ethics.

The extent to which he broadened the scope of the theatre is shown by the range of his plays—e.g., Los intereses creados (performed 1903, published 1907; The Bonds of Interest, performed 1919), his most celebrated work, based on the Italian commedia dell’arte; Los malhechores del bien (performed 1905; The Evil Doers of Good); La noche del sábado (performed 1903; Saturday Night, performed 1926); and La malquerida (1913; “The Passion Flower”), a rural tragedy with the theme of incest. La malquerida was his most successful play in Spain and in North and South America. Señora Ama (1908), said to be his own favourite play, is an idyllic comedy set among the people of Castile.

In 1928 his play Para el cielo y los altares (“Toward Heaven and the Altars”), prophesying the fall of the Spanish monarchy, was prohibited by the government. During the Spanish Civil War Benavente lived in Barcelona and Valencia and was for a time under arrest. In 1941 he reestablished himself in public favour with Lo increíble (“The Incredible”). His extraordinary productivity as a dramatist (he wrote more than 150 plays) recalled Spain’s Golden Age and the prolific writer Lope de Vega. With the exception, however, of the harsh tragedy La infanzona (1948; “The Ancient Noblewoman”) and El lebrel del cielo (1952), inspired by Francis Thompson’s poem “Hound of Heaven,” Benavente’s later works did not add much to his fame.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#920 2021-06-10 00:08:09

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 48,424

Re: crème de la crème

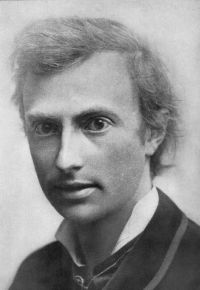

886) William Butler Yeats

William Butler Yeats, (born June 13, 1865, Sandymount, Dublin, Ireland—died January 28, 1939, Roquebrune-Cap-Martin, France), Irish poet, dramatist, and prose writer, one of the greatest English-language poets of the 20th century. He received the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1923.

Yeats’s father, John Butler Yeats, was a barrister who eventually became a portrait painter. His mother, formerly Susan Pollexfen, was the daughter of a prosperous merchant in Sligo, in western Ireland. Through both parents Yeats (pronounced “Yates”) claimed kinship with various Anglo-Irish Protestant families who are mentioned in his work. Normally, Yeats would have been expected to identify with his Protestant tradition—which represented a powerful minority among Ireland’s predominantly Roman Catholic population—but he did not. Indeed, he was separated from both historical traditions available to him in Ireland—from the Roman Catholics, because he could not share their faith, and from the Protestants, because he felt repelled by their concern for material success. Yeats’s best hope, he felt, was to cultivate a tradition more profound than either the Catholic or the Protestant—the tradition of a hidden Ireland that existed largely in the anthropological evidence of its surviving customs, beliefs, and holy places, more pagan than Christian.

In 1867, when Yeats was only two, his family moved to London, but he spent much of his boyhood and school holidays in Sligo with his grandparents. This country—its scenery, folklore, and supernatural legend—would colour Yeats’s work and form the setting of many of his poems. In 1880 his family moved back to Dublin, where he attended the high school. In 1883 he attended the Metropolitan School of Art in Dublin, where the most important part of his education was in meeting other poets and artists.

Meanwhile, Yeats was beginning to write: his first publication, two brief lyrics, appeared in the Dublin University Review in 1885. When the family moved back to London in 1887, Yeats took up the life of a professional writer. He joined the Theosophical Society, whose mysticism appealed to him because it was a form of imaginative life far removed from the workaday world. The age of science was repellent to Yeats; he was a visionary, and he insisted upon surrounding himself with poetic images. He began a study of the prophetic books of William Blake, and this enterprise brought him into contact with other visionary traditions, such as the Platonic, the Neoplatonic, the Swedenborgian, and the alchemical.

Yeats was already a proud young man, and his pride required him to rely on his own taste and his sense of artistic style. He was not boastful, but spiritual arrogance came easily to him. His early poems, collected in ‘The Wanderings of Oisin, and Other Poems’ (1889), are the work of an aesthete, often beautiful but always rarefied, a soul’s cry for release from circumstance.

Yeats quickly became involved in the literary life of London. He became friends with William Morris and W.E. Henley, and he was a cofounder of the Rhymers’ Club, whose members included his friends Lionel Johnson and Arthur Symons. In 1889 Yeats met Maud Gonne, an Irish beauty, ardent and brilliant. From that moment, as he wrote, “the troubling of my life began.” He fell in love with her, but his love was hopeless. Maud Gonne liked and admired him, but she was not in love with him. Her passion was lavished upon Ireland; she was an Irish patriot, a rebel, and a rhetorician, commanding in voice and in person. When Yeats joined in the Irish nationalist cause, he did so partly from conviction, but mostly for love of Maud. When Yeats’s play Cathleen ni Houlihan was first performed in Dublin in 1902, she played the title role. It was during this period that Yeats came under the influence of John O’Leary, a charismatic leader of the Fenians, a secret society of Irish nationalists.

After the rapid decline and death of the controversial Irish leader Charles Stewart Parnell in 1891, Yeats felt that Irish political life lost its significance. The vacuum left by politics might be filled, he felt, by literature, art, poetry, drama, and legend. ‘The Celtic Twilight’ (1893), a volume of essays, was Yeats’s first effort toward this end, but progress was slow until 1898, when he met Augusta Lady Gregory, an aristocrat who was to become a playwright and his close friend. She was already collecting old stories, the lore of the west of Ireland. Yeats found that this lore chimed with his feeling for ancient ritual, for pagan beliefs never entirely destroyed by Christianity. He felt that if he could treat it in a strict and high style, he would create a genuine poetry while, in personal terms, moving toward his own identity. From 1898, Yeats spent his summers at Lady Gregory’s home, Coole Park, County Galway, and he eventually purchased a ruined Norman castle called Thoor Ballylee in the neighbourhood. Under the name of the Tower, this structure would become a dominant symbol in many of his latest and best poems.

In 1899 Yeats asked Maud Gonne to marry him, but she declined. Four years later she married Major John MacBride, an Irish soldier who shared her feeling for Ireland and her hatred of English oppression: he was one of the rebels later executed by the British government for their part in the Easter Rising of 1916. Meanwhile, Yeats devoted himself to literature and drama, believing that poems and plays would engender a national unity capable of transfiguring the Irish nation. He (along with Lady Gregory and others) was one of the originators of the Irish Literary Theatre, which gave its first performance in Dublin in 1899 with Yeats’s play The Countess Cathleen. To the end of his life Yeats remained a director of this theatre, which became the Abbey Theatre in 1904. In the crucial period from 1899 to 1907, he managed the theatre’s affairs, encouraged its playwrights (notably John Millington Synge), and contributed many of his own plays. Among the latter that became part of the Abbey Theatre’s repertoire are ‘The Land of Heart’s Desire’ (1894), ‘Cathleen ni Houlihan’ (1902), ‘The Hour Glass’ (1903), ‘The King’s Threshold’ (1904), ‘On Baile’s Strand’ (1905), and ‘Deirdre’ (1907).

Yeats published several volumes of poetry during this period, notably ‘Poems’ (1895) and ‘The Wind Among the Reeds’ (1899), which are typical of his early verse in their dreamlike atmosphere and their use of Irish folklore and legend. But in the collections ‘In the Seven Woods’ (1903) and ‘The Green Helmet’ (1910), Yeats slowly discarded the Pre-Raphaelite colours and rhythms of his early verse and purged it of certain Celtic and esoteric influences. The years from 1909 to 1914 mark a decisive change in his poetry. The otherworldly, ecstatic atmosphere of the early lyrics has cleared, and the poems in ‘Responsibilities: Poems and a Play’ (1914) show a tightening and hardening of his verse line, a more sparse and resonant imagery, and a new directness with which Yeats confronts reality and its imperfections.

In 1917 Yeats published ‘The Wild Swans at Coole’. From then onward he reached and maintained the height of his achievement—a renewal of inspiration and a perfecting of technique that are almost without parallel in the history of English poetry. ‘The Tower’ (1928), named after the castle he owned and had restored, is the work of a fully accomplished artist; in it, the experience of a lifetime is brought to perfection of form. Still, some of Yeats’s greatest verse was written subsequently, appearing in ‘The Winding Stair’ (1929). The poems in both of these works use, as their dominant subjects and symbols, the Easter Rising and the Irish civil war; Yeats’s own tower; the Byzantine Empire and its mosaics; Plato, Plotinus, and Porphyry; and the author’s interest in contemporary psychical research. Yeats explained his own philosophy in the prose work ‘A Vision’ (1925, revised version 1937); this meditation upon the relation between imagination, history, and the occult remains indispensable to serious students of Yeats despite its obscurities.

In 1913 Yeats spent some months at Stone Cottage, Sussex, with the American poet Ezra Pound acting as his secretary. Pound was then editing translations of the nō plays of Japan, and Yeats was greatly excited by them. The nō drama provided a framework of drama designed for a small audience of initiates, a stylized, intimate drama capable of fully using the resources offered by masks, mime, dance, and song and conveying—in contrast to the public theatre—Yeats’s own recondite symbolism. Yeats devised what he considered an equivalent of the nō drama in such plays as ‘Four Plays for Dancers’ (1921), ‘At the Hawk’s Well’ (first performed 1916), and several others.

In 1917 Yeats asked Iseult Gonne, Maud Gonne’s daughter, to marry him. She refused. Some weeks later he proposed to Miss George Hyde-Lees and was accepted; they were married in 1917. A daughter, Anne Butler Yeats, was born in 1919, and a son, William Michael Yeats, in 1921.

In 1922, on the foundation of the Irish Free State, Yeats accepted an invitation to become a member of the new Irish Senate: he served for six years. In 1923 he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature. Now a celebrated figure, he was indisputably one of the most significant modern poets. In 1936 his ‘Oxford Book of Modern Verse, 1892–1935’, a gathering of the poems he loved, was published. Still working on his last plays, he completed ‘The Herne’s Egg’, his most raucous work, in 1938. Yeats’s last two verse collections, ‘New Poems and Last Poems and Two Plays’, appeared in 1938 and 1939 respectively. In these books many of his previous themes are gathered up and rehandled, with an immense technical range; the aged poet was using ballad rhythms and dialogue structure with undiminished energy as he approached his 75th year.

Yeats died in January 1939 while abroad. Final arrangements for his burial in Ireland could not be made, so he was buried at Roquebrune, France. The intention of having his body buried in Sligo was thwarted when World War II began in the autumn of 1939. In 1948 his body was finally taken back to Sligo and buried in a little Protestant churchyard at Drumcliffe, as he specified in “Under Ben Bulben,” in his ‘Last Poems’, under his own epitaph: “Cast a cold eye/On life, on death./Horseman, pass by!”

Had Yeats ceased to write at age 40, he would probably now be valued as a minor poet writing in a dying Pre-Raphaelite tradition that had drawn renewed beauty and poignancy for a time from the Celtic revival. There is no precedent in literary history for a poet who produces his greatest work between the ages of 50 and 75. Yeats’s work of this period takes its strength from his long and dedicated apprenticeship to poetry; from his experiments in a wide range of forms of poetry, drama, and prose; and from his spiritual growth and his gradual acquisition of personal wisdom, which he incorporated into the framework of his own mythology.

Yeats’s mythology, from which arises the distilled symbolism of his great period, is not always easy to understand, nor did Yeats intend its full meaning to be immediately apparent to those unfamiliar with his thought and the tradition in which he worked. His own cyclic view of history suggested to him a recurrence and convergence of images, so that they become multiplied and enriched; and this progressive enrichment may be traced throughout his work. Among Yeats’s dominant images are Leda and the Swan; Helen and the burning of Troy; the Tower in its many forms; the sun and moon; the burning house; cave, thorn tree, and well; eagle, heron, sea gull, and hawk; blind man, lame man, and beggar; unicorn and phoenix; and horse, hound, and boar. Yet these traditional images are continually validated by their alignment with Yeats’s own personal experience, and it is this that gives them their peculiarly vital quality. In Yeats’s verse they are often shaped into a strong and proud rhetoric and into the many poetic tones of which he was the master. All are informed by the two qualities which Yeats valued and which he retained into old age—passion and joy.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#921 2021-06-12 00:30:26

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 48,424

Re: crème de la crème

887) Władysław Stanisław Reymont

Władysław Stanisław Reymont, Reymont also spelled Rejment, (born May 7, 1867, Kobiele Wielkie, Poland, Russian Empire [now in Poland]—died December 5, 1925, Warsaw, Poland), Polish writer and novelist who was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1924.

Reymont never completed his schooling but was at various times in his youth a shop apprentice, a lay brother in a monastery, a railway official, and an actor. His early writing includes ‘Ziemia obiecana’ (1899; The Promised Land; filmed 1974), a story set in the rapidly expanding industrial town of Łódz and depicting the lives and psychology of the owners of the textile mills there. His two early novels ‘Komediantka’ (1896; The Comedienne) and ‘Fermenty’ (1897; “The Ferments”) were based on his own theatrical experience, while his short stories from peasant life show the strong influence of Naturalism. The novel Chłopi, 4 vol. (1904–09; The Peasants; filmed 1973), is a chronicle of peasant life during the four seasons of a year. Written almost entirely in peasant dialect, it has been translated into many languages and won for Reymont the Nobel Prize.

Reymont’s later work was less expressive but reflected the variety of his interests, including his view of the spiritualist movement in ‘Wampir’ (1911; “Vampire”) and his image of Poland at the beginning of the partition process at the end of the 18th century, ‘Rok 1794’, 3 vol. (1913–18; “The Year 1794”).

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#922 2021-06-14 00:07:28

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 48,424

Re: crème de la crème

888) Grazia Deledda

Grazia Deledda (Grazia Maria Cosima Damiana Deledda), (born Sept. 27, 1871, Nuoro, Sardinia, Italy—died Aug. 15, 1936, Rome), novelist who was influenced by the verismo (q.v.; “realism”) school in Italian literature. She was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1926.

Deledda married very young and moved to Rome, where she lived quietly, frequently visiting her native Sardinia. With little formal schooling, at age 17 Deledda wrote her first stories, based on sentimental treatment of folklore themes. With ‘Il vecchio della montagna’ (1900; “The Old Man of the Mountain”) she began to write about the tragic effects of temptation and sin among primitive human beings.